BASE HEADER

Canalside Development Plan Document

(1) SECTION 2 Context

(2) Vision:

To increase the economic, environmental and social benefits of the canals and their environs with well designed new development on underutilised, vacant or derelict sites, taking into account the special character, qualities and history of the waterways and the protection afforded by the Canal Conservation Area.

Support will be given to the protection of heritage assets and the enhancement of green and blue corridors, the protection of biodiversity and habitats of the waterways and the improvement of water quality, recognising the contribution to health and wellbeing for users.

Tourism and facilities for boat and other leisure users will be generally supported as well as the use of canals and towpaths as a sustainable transport route for both goods, services and people.

Improvements to and the protection of canal infrastructure will be extremely important when considering new development adjacent to the canals and along towpaths.

There is recognition of the contribution that canals can make as a renewable energy resource in the heating and cooling of buildings and as a source of water for commercial, agricultural and public consumption.

2.1 The Canals that run through Warwick District are:

The Grand Union Canal:

The Grand Union Canal runs east to west through the southern part of the district from a point just to the east of the Fosse Way beyond Radford Semele, to the point where it links to the Stratford Canal south east of Kingswood and on to the edge of the Warwick District Boundary, east of Dorridge. The more urban section of canal runs through the towns of Leamington Spa and Warwick.

The South and North Stratford Canals:

The South Stratford Canal runs south to north until it reaches Kingswood, where it turns west through Lapworth and becomes the North Stratford Canal, until it leaves the district at Hockley Heath.

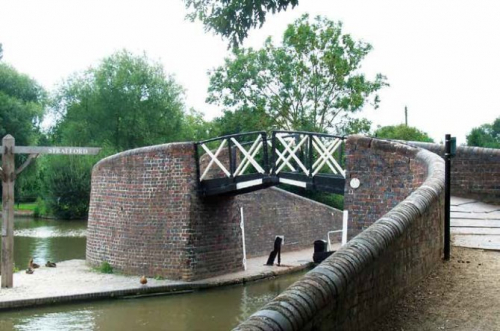

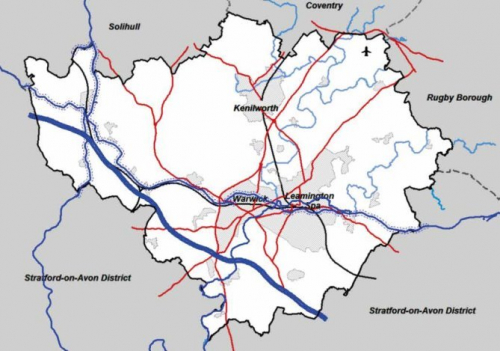

Waterways through Warwick District

Waterways through Warwick District

2.2 A Brief History of Canals in Warwick District

The Romans first built canals in this country for the same purpose for which they were required in the 18th Century; to move heavy cargoes from point A to point B and to transport large amounts of water across valleys and hills. Most of the Roman canals were set up as irrigation systems, for land drainage or to link rivers. The Fossdyke in Lincolnshire was built around 120 AD, to connect the River Witham to the River Trent and is probably the oldest canal in Britain.

2.3 In the 18th century it became clear that for the new industries which were emerging as a result of the Industrial Revolution an efficient way of transporting raw materials and other cargo was necessary. The Government was lobbied to pass Acts which enabled the construction of canals to commence with money raised by the new entrepreneurs forging new businesses which needed to move goods quickly from the point of origin to the major cities of Great Britain.

2.4 The work force for digging the 'cuts', where the landscape was literally cut into to enable the water to be channelled along, largely came from Ireland and the industrial north of England and became known as the 'navigators' or 'navvies'; a term still in use today for those labouring on building projects.

2.5 Following the natural terrain of the land, the canals often skirted hills and valleys, but when the water level inevitably had to change to traverse the landscape, locks were built. These were used to great effect to raise or release water levels to enable the next level to be navigated. Where necessary, a staircase of locks was used, as in the case of the 'Hatton Flight' or the 'Stairway to Heaven' locally.

The Hatton Flight of locks today (WDC)

2.6 The Grand Junction Canal received its Act in 1793 and was fully operational by 1805. The original Grand Junction Canal ran from Birmingham to London, was 137 miles long and had 166 locks. It was built at a time when there were no railway connections and roads were poor, to improve communications between Birmingham and the Midlands and London and to serve businesses which had emerged from the industrial revolution and which were heavily reliant on a constant supply of coal.

2.7 The Grand Junction was built as a broad canal in the south where 14ft boats could be accommodated, but at its northern end it joined the Oxford Canal which was narrow and the canals into Birmingham were also narrow. It was generally therefore used only by narrow boats, except at the London end. The advent of the railways meant that the waterways were forced to adapt in order to survive.

2.8 The section through this district was designed for narrow boats and was built by two companies; the Warwick & Napton Canal and the Warwick & Birmingham Canal. Working together meant that the canal profited until 1838 when the railway was built bringing direct competition.

2.9 In 1894 the Grand Junction purchased the canals which now comprise the 'Leicester Line'. In 1929 the Regent's, Grand Junction and the two Warwick Canals merged and became the 'Grand Union Canal'.

2.10 The new company, with the help of government loans, modernised this part of the system to enable broad-beamed boats to work between London and Birmingham. Dredging was carried out and the banks protected with concrete strengthening, bridges widened or replaced, and narrow locks replaced with broad locks. Completed in 1937 much of the canal remained too shallow for broad boats to pass each other and unable to pass in tunnels however. Narrow boat traffic increased in the short term, but post-war with canalside factories no longer using coal as a fuel or having it brought in by other transport methods, the canals declined. Loading boats along the Grand Union Canal was phased out in the 1930's and although commercial carrying continued until the early 1970's, the decline had set in post WWII.

2.11 How The Use of Canals Has Changed

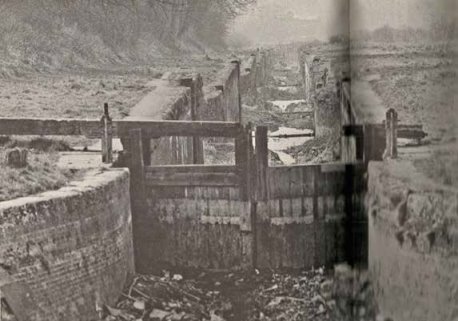

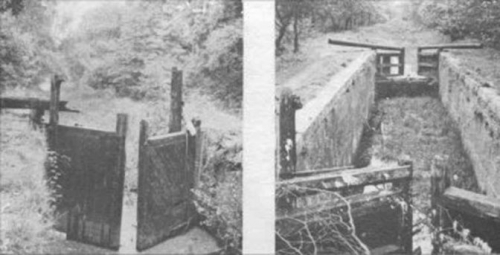

Having been built for trading purposes to transport large, bulky items with relative ease, the canals fell out of favour with the coming of the railway and a much improved and extended road network. With no real purpose, those canals that fared best became a haven for wildlife and a place for quiet contemplation and angling/water based leisure as they are today. Those that fared less well became overgrown, abandoned and totally disused other than as rubbish tips. An extensive history of the local canals can be found in the work connected with the designation of the Conservation Area (see 3.1 for link).

The Kennet and Avon Canal, Devizes (from 'Canal' by Anthony Burton and Derek Pratt)

Basingstoke Canal near Pirbright, Surrey (Dr Neil Clifton)

Liskeard and Looe Union Canal (David Stowell))

Above Lock No. 2 Basingstoke Canal (Dr Neil Clifton)

2.12 Today, with a renewal of interest in the canals and in canal travel for pleasure, there are far more uses for canals than ever before. From those wishing to travel in their leisure time on narrowboats and other craft, to walkers, cyclists and anglers, the resurgence in interest has sparked off a whole new demand for canal use and activities. Some canal based small businesses have also sprung up creating a new sense of purpose and embracing the concept of travel as part of that business for some.

2.13 The importance of canals is increasing in terms of use as a resource too. Not only does the canal act as a waterway to convey people and to some extent, goods, but it also acts as a reservoir, storing water for times of drought caused increasingly by climate change. Water is abstracted on the canal system for both agriculture and commercial uses. There are real issues around the level of topping up and abstraction, since there are more applications for licences to abstract water made year on year. The level of water needs to be maintained to allow navigation and to keep the water clean and aerated enough to support fish and other animal and plant life.

2.14 There are wide ranging health and wellbeing benefits provided by use of the canal and towpaths. Both physical and mental health can be improved by reducing stress and improving relaxation. Mental health, especially symptoms brought on by depression and loneliness, are being increasingly subjected to 'social prescribing' by GP's which involves directing a patient towards an activity or community group. What is more, it's a free resource. ("canals prescribed by GP's to combat depression", The Telegraph, May 2018)

In Buckinghamshire, canalside walking is being promoted to patients suffering from high blood pressure, depression and lung problems.

2.15 What Has Happened Elsewhere?

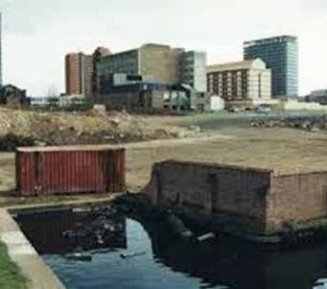

An excellent example locally of the resurgence in interest in the canal network and the way in which the canal is utilised, is Birmingham and in particular around the Gas Street Basin and Brindley Place area where a substantial amount of investment has regenerated the canal and the surrounding district. The following photographs illustrate the difference made. Note that buildings now face onto the canal rather than backing onto it as before.

Brindley Place before work was carried out (UrbanBuildings)

Before Work Started in 1990s at Brindley Place (Birmingham Express & Star)

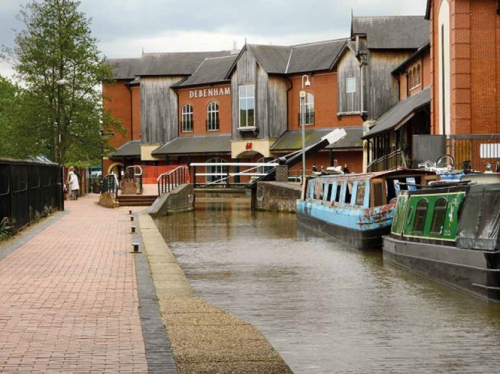

Banbury's Castle Quay – note the architectural features reflecting previous buildings/uses (Geograph)